About 300 million years ago, during the Carboniferous period and well before dinosaurs dominated the planet, the world was home to bizarre and enormous creatures. Vast vegetation populated marshy woodlands, amphibious animals crawled over damp terrain—and gigantic arthropods roamed the land as well.

Arthropleura

roamed the land.

This massive, centipede-esque organism extended more than two meters in length, rendering it the biggest known terrestrial invertebrate.

The largest insect in the world gets a head

Arthopleura stands as the biggest known terrestrial invertebrate, and it was truly frightening. Imagine an entity from a nightmare: forty sets of legs paired with jaw-like appendages resembling limbs. Visualize a giant version of a millipede—about the length of a vehicle, weighing more than 100 pounds (or 45 kilograms)—roaming through forests, and you’d be fairly accurate in picturing Arthopleura.

This species was quite prevalent since paleontologists discovered numerous fossils of it along with the imprints it made on the ground. Nonetheless, we had not come across a complete skull until now. As such, much of our understanding of Arthopleura has been derived from fragmented remains.

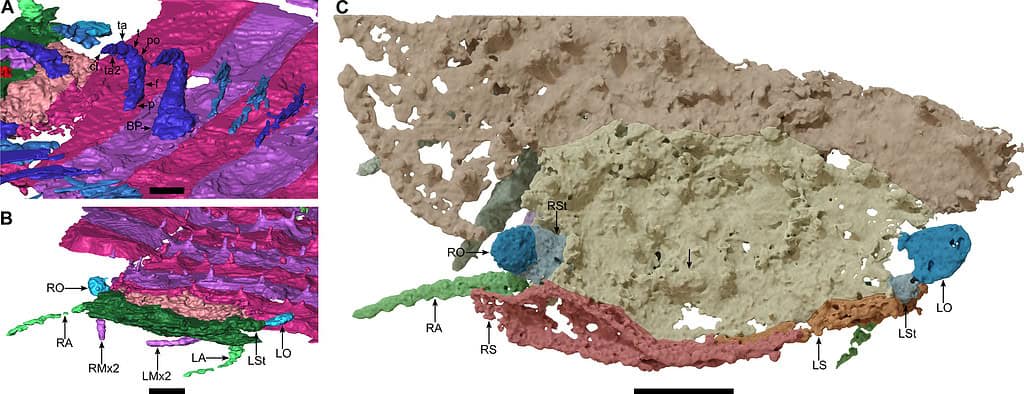

The recent study centered on juvenile Arthropleura remains encased within iron-filled concretions discovered at Montceau-les-Mines, a remarkable fossil location known for revealing intricate details about numerous prehistoric organisms. By employing sophisticated scanning methods, the investigative group was able to recreate the creature’s head and mandibles, providing the clearest depiction to date of this massive ancient arthropod’s structure—including its facial features.

Staring directly at its face

Led by Mickaël Lhéritier from the Université Claude Bernard, the team of paleontologists examined the remarkably intact remains of multiple young specimens. Using tomographic imaging methods, they reconstructed the facial features of these ancient beings.

Their analysis revealed that

Arthropleura

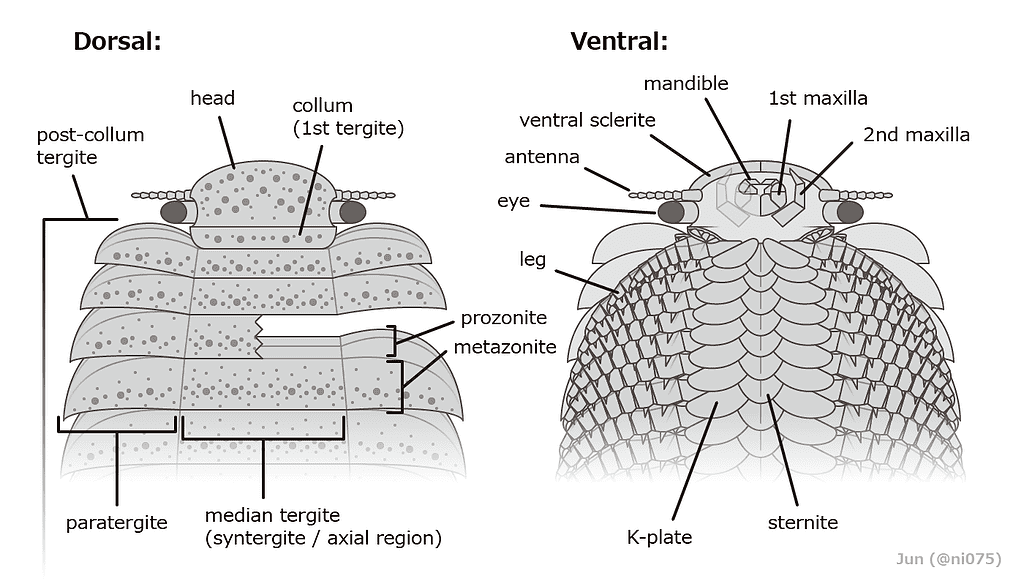

featured a robust, disc-shaped plate known as a collum protecting its head. Additionally, it had protruding eyes on stems, jointed feelers, and jaws designed for grinding. These characteristics indicate a preference for vegetation and decomposing organic matter; however, certain scientists believe it might have occasionally engaged in scavenging activities.

James Lamsdell, an associate professor of paleobiology at West Virginia University, wrote an

accompanying article

It’s safe to say that many aspects of Arthopleura remain mysterious. We’re unsure about its diet, as well as its precise habitat. While the forest floor seems the most likely environment for it, it might have also frequented aquatic settings akin to an alligator.

“Without direct evidence from digestive tracts, it is still unclear exactly what Arthropleura ate,” he wrote. “The respiratory organs also remain unknown, leaving the possibility that Arthropleura was aquatic.”

The combination of a heavily armored body and many legs would have made Arthropleura well-suited to navigating through thick vegetation, possibly burrowing through leaf litter in search of food. Its slow movement likely made it a poor predator, reinforcing the idea that it was a herbivore or detritivore. Without better fossils, however, it’s hard to say for sure.

A gentle giant?

Determining Arthropleura’s precise evolutionary relationships is also a long-standing challenge for researchers. The general idea is that it was a myriapod (a group that includes millipedes, centipedes, and their relatives). But where exactly it fits on the evolutionary tree is less clear. The new study used

total-evidence phylogenetics

a technique that merges both physical (morphological) and molecular information to elucidate evolutionary connections.

Similar to millipedes, Arthopleura possessed seven-segmented antennae along with a specialized collum. Yet, akin to centipedes, it featured completely enclosed mandibles and leg-like mouthparts known as maxillae. According to this study, Arthopleura can be classified as a “millipede stem-group” entity—indicating shared ancestral lineage with contemporary millipedes without being one of them directly. It could potentially represent either part of an early group linked closely to millipedes or serve as a bridge species transitioning from millipedes towards centipedes.

But this begs the question: why did it grow so large?

Modern arthropods, like insects and millipedes, are much smaller. Naturally, this leads scientists to wonder what environmental factors allowed their ancient relatives to grow so large. One theory is that high levels of oxygen in the Carboniferous atmosphere, caused by the extensive forests, allowed for larger body sizes in arthropods, which rely on diffusion through their exoskeletons to breathe.

Additionally, the absence of large terrestrial vertebrates during the Carboniferous may have allowed arthropods like Arthropleura to dominate the landscape without competition from other large herbivores. However, as vertebrates evolved and diversified, including the appearance of early reptiles, these giant arthropods eventually faced new challenges that likely contributed to their extinction by the end of the Permian period, some 50 million years after they first emerged.

The study “Head anatomy and phylogenomics show the Carboniferous giant

Arthropleura

belonged to a millipede-centipede group”

was published

in

Science Advances

.

This story originally appeared on

ZME Science

. Want to get smarter every day?

Subscribe to our newsletter

And remain at the forefront with the newest scientific discoveries.