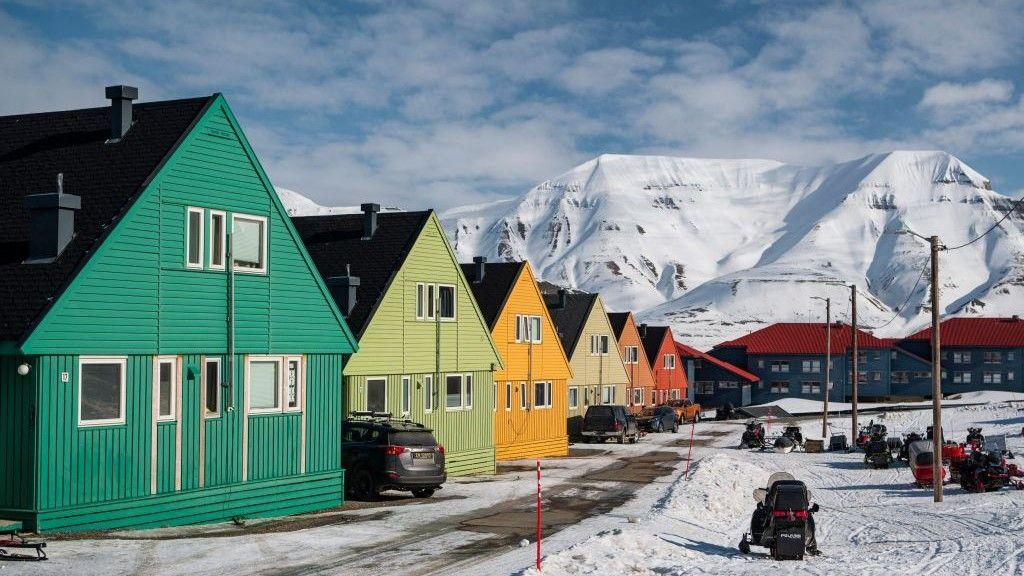

Far north of the Arctic Circle, the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard sits midway between continental Norway and the North Pole.

Frozen, mountainous, and remote, it’s home to hundreds of polar bears and a couple of sparse settlements.

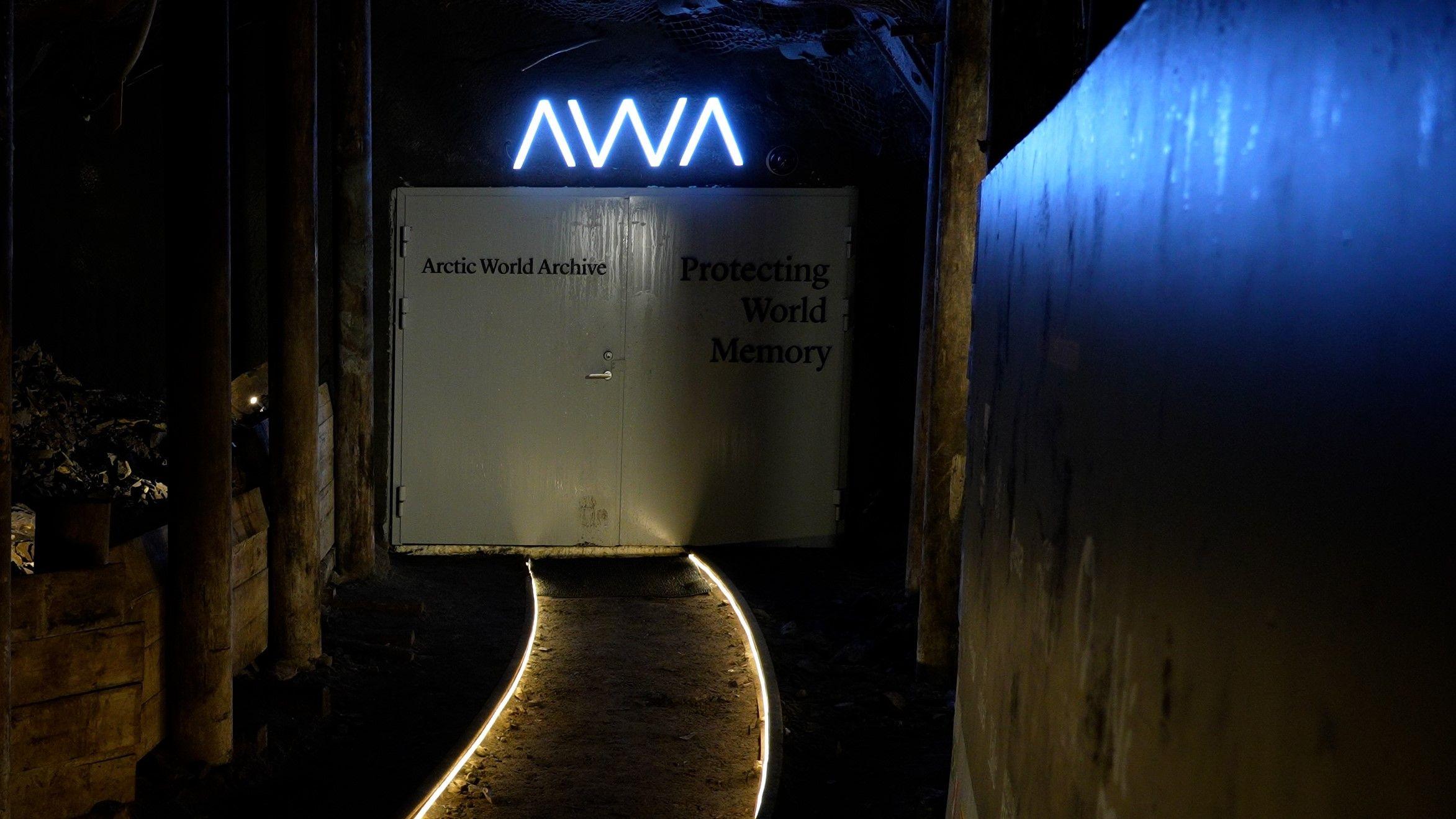

One of them is Longyearbyen, which holds the title of being the planet’s most northerly town, and situated just beyond this community, within an abandoned coalmine, lies The Arctic World Archive (AWA)—an underground facility designed for storing information.

Customers pay to have their data stored on film and kept in the vault, for potentially hundreds of years.

“This is where we ensure that information withstands technological outdatedness, the passage of time, and deterioration. That’s our objective,” explains founder Rune Bjerkestrand as he leads the tour indoors.

Activating our headlamps, we made our way down a dim tunnel and traced the ancient railway lines for 300 meters into the mountain, arriving at the archives’ steel entrance.

Inside the vault, stands a shipping container stacked with silver packets, each containing reels of film, on which the data is stored.

“It’s a lot of memories, a lot of heritage,” Mr Bjerkestrand says.

From digitized artwork and literature to music, movies, you name it, everything is included.

Since the archive’s launch eight years ago, more than 100 deposits have been made by institutions, companies and individuals, from 30-plus countries.

Among the many digitised artefacts are 3D scans and models of the Taj Mahal; tranches of ancient manuscripts from the Vatican Library; satellite observations of Earth from space; and Norway’s treasured painting, the Scream, by Edvard Munck.

The AWA operates commercially and depends on technology supplied by the Norwegian data conservation firm Piql, where Mr. Bjerkestrand is also at the helm.

It drew inspiration from the Global Seed Vault, which lies just a short distance away. This facility serves as a storage site for seeds, allowing recovery of various crops following either natural or human-induced calamities.

“Currently, there are numerous threats to information and data,” stated Mr. Bjerkstand. “This includes terrorism, warfare, and cyber hackers.”

In his view, Svalbard is an ideal location for setting up a secure data storage facility.

It’s situated at quite a distance from everything! A place distant from conflicts, crises, terrorism, and calamities. Could anything feel more secure!

Beneath the surface, it’s dim, arid, and cold, with consistently below-freezing temperatures throughout the year; circumstances that Mr. Bjerkestrand asserts are perfect for preserving the film intact for hundreds of years.

If global warming leads to the extensive melting of the Arctic permafrost, he asserts that the vault remains sturdy enough to safeguard its contents.

In the rear of the room, an additional massive metallic container holds GitHub’s Code Vault.

The software developer has stored numerous reels of open-source code here, serving as foundational elements for computer operating systems, software, websites, and applications.

The collection includes programming languages, artificial intelligence tools, along with all actively used public repositories on the platform. These resources are contributed by its 150 million users.

“Securing the future of software has become utterly essential for humanity due to its significant role in our daily routines,” says GitHub’s Chief Operating Officer, Kyle Daigle, during an interview with Dailyexe.

He mentioned that his company has looked into multiple options for long-term storage, adding that several hurdles remain. “While some of our current systems can last for an extended period, they require specific technologies to access their contents,” he explained.

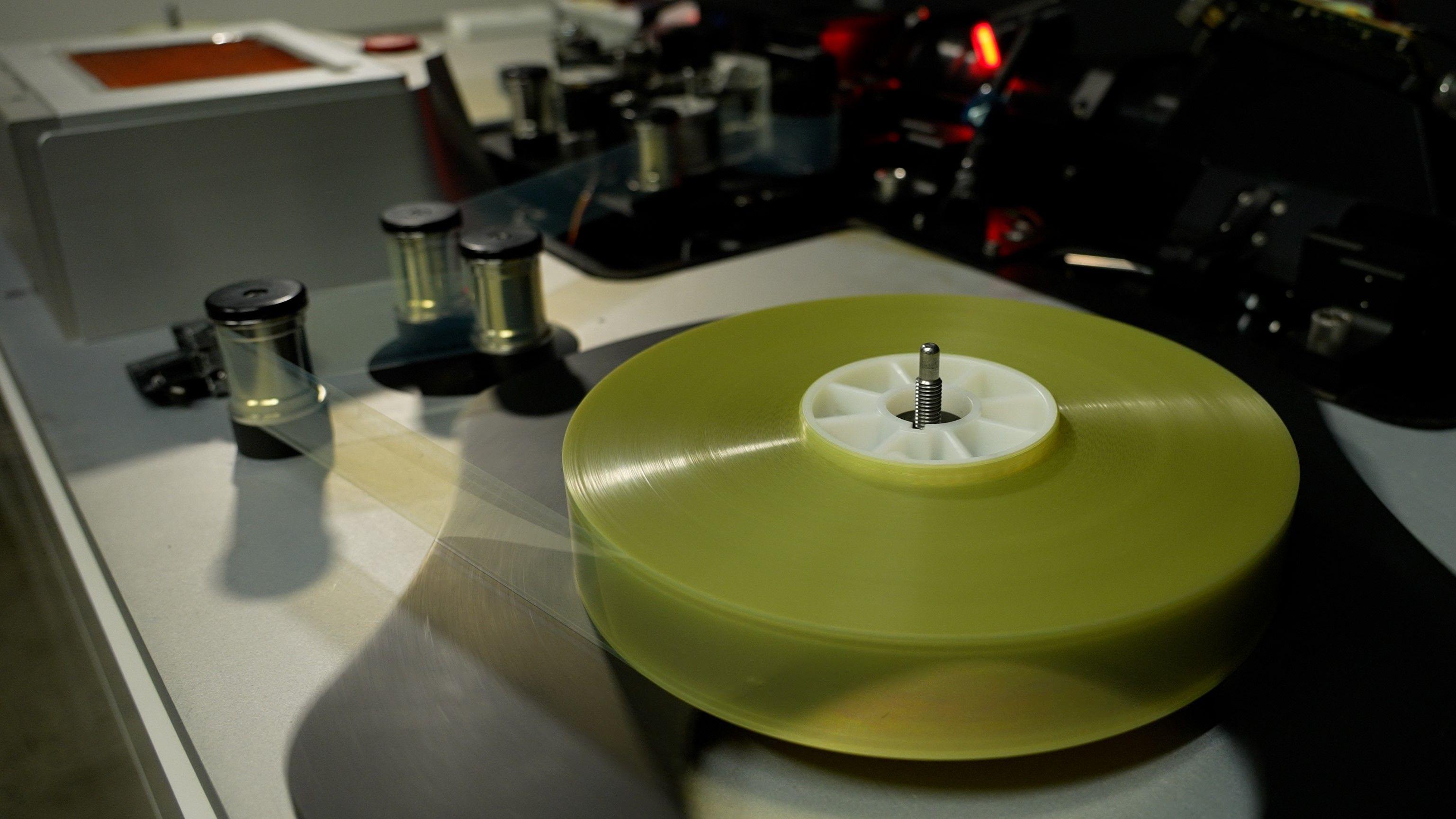

At Piql’s base located in the south of Norway, information files are transformed into images on photosensitive film.

“As the film runs through the spool at his fingertips, senior product developer Alexey Mantsev explains, ‘Data consists of sequences of bits and bytes,'” he elucidates.

We transform the series of bits we receive from client data into visual images. Each image, or frame, comprises approximately eight million pixels.

Once these images are exposed and developed, the processed film appears grey, but viewed more closely, it’s similar to a mass of tiny QR codes.

The information can’t be deleted or changed, and is easily retrievable explains Mr Mantsev.

“We can scan it back, and decode the data just the same way as reading data from a hard drive, but we will be reading data from the film.”

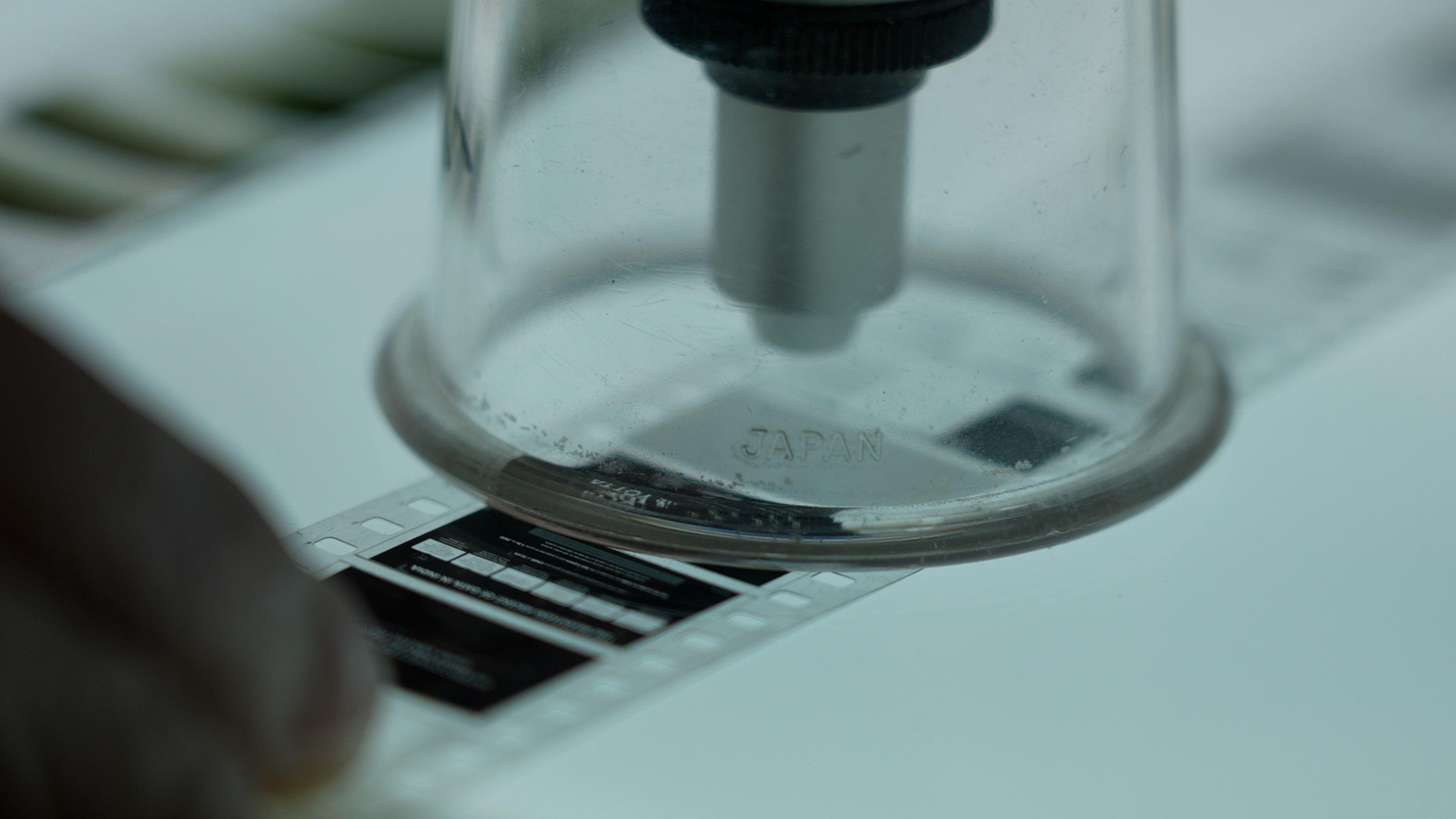

One key question arising with long-term storage methods, is whether people will understand what has been preserved and how to recover it, centuries into the future.

That’s a scenario Piql has also thought about, and so a guide that can be magnified and read optically, is printed onto the film, as well.

Every day more data is being used and generated than ever before, but experts have long warned of a

potential “digital Dark Age”

, as technological advances render previous software and hardware obsolete.

This might imply that the file types and formats we currently employ may end up like the obsolete floppy disks and DVD drives from earlier times.

A multitude of companies provide extended period data retention services.

LTO (Linear Tape Open) cassettes made from magnetic tape represent the predominant format currently used for storage; however, emerging advancements aim to transform data preservation methods.

For instance, Microsoft’s Project Silica has created 2-millimeter thick pieces of glass, where portions of information are transmitted using intense lasers.

In the meantime, researchers from the University of Southampton have developed what they call a 5D memory crystal. This technology has managed to store an extensive record of the human genome.

That has also been positioned in the

Memory of Mankind repository

, an additional vault protecting historical papers, located within a salt mine in Austria.

The Arctic World Archive accepts deposits three times annually, and during the recent visit by Dailyexe, recordings of threatened languages along with the manuscripts of composer Chopin were among the newest materials stored within the vault.

Christian Clauwers, a photographer capturing the islands of the South Pacific facing threats from rising seas, has also contributed his documentation efforts.

“I deposited footage and photography, visual witnesses of the Marshall Islands,” he says.

“The highest point of the island is three meters, and they’re facing huge impact of climate change.”

“It was really humbling and surreal,” says archivist Joanne Shortland, head of Heritage Collections at the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust, after depositing records, engineers’ drawings and photographs of historic car models.

“I have all these formats that are becoming obsolete.

Continuous changes in the file format should be made to ensure accessibility for up to 20 or even 30 years from now. The digital realm presents numerous challenges.

More Technology of Business

- Who will come out on top in the competition to create a humanoid robot?

- Is cocoa-free chocolate necessary, and is it enjoyable?

- Finnish defense companies amped up on steroids